Conversations

- The IABA SNS Blog

Wellness Through Womyn's Circle

Tala Khanmalek and Maria Faini in conversation

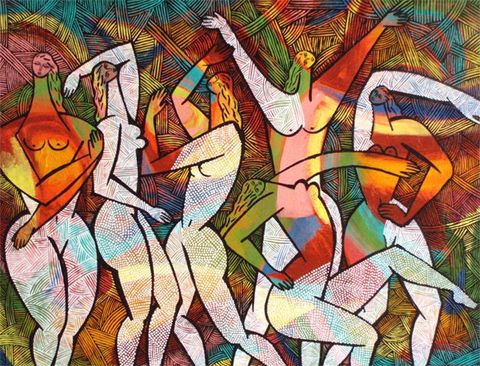

The cover image of the book collection emerging from Womyn's Circle. Artist: Michelle Robinson

Wellbeing: creating Womyn's Circle

Maria Faini (MF): What originally led you to form the womyn’s circle? What needs (graduate school or community related) compelled you to begin the process and what did you originally imagine for the circle?

Tala Khanmalek (TK): I was diagnosed with a brain tumor after my first year of grad school. I opted out of pharmaceuticals in hopes of a more holistic treatment plan and immediately encountered two major problems: student health insurance doesn't cover "alternative medicine" of any kind and regardless, student health centers aren't equipped to address health issues that require specialized care. I was in a situation where I was dependent on the university for healthcare services yet it totally and completely, not to mention disgracefully, failed to be an adequate provider. I might have taken a leave of absence if I wasn't also dependent on the university for health insurance and financial aid, both of which I desperately needed now that health-related expenses were a part of my everyday life. With my wellbeing on the line, I needed a solution quick and fast. In addition to scrounging for community-based resources in the East Bay as well as learning about and becoming involved in the local healing justice movement, I decided to gather the community of womyn I already knew. While I originally imagined for us to simply share experiential knowledge about self-care, the sheer and incredibly palpable necessity of the exchange led me to host and eventually create a loose structure for a monthly meeting at my studio apartment. What started because of a personal crisis immediately transformed into an urgent community-care demand, if you will, which (of course) inevitably led us to consider the social factors impacting our wellbeing, especially since womyn of color comprised a majority of the group.

MF: Tala, this is a tremendous circumstance. Thank you for being willing to share this sensitive and critical information.

In terms of follow up questions, I’ve been thinking about the ways your diagnosis and subsequent decisions for your well being affected your sense of self, if they affected this sense for you, and how you addressed the experience in womyn’s circle. I ask these questions because my sense of my own identity is always in flux, at times far more than I’m comfortable facing, my understanding of my health and well being plays a significant role in this always evolving understanding. How did your choice to forego insurance-approved treatment affect the way you felt represented and understood in the university environment? And in what specific ways did you incorporate these experiences into your participation in the womyn’s circle? Please elaborate only if you feel comfortable doing so.

TK: Well, those are precisely the things I was trying to figure out in a community.

At the time, the medical industrial complex was creating the terms of definition for me. One of the most empowering moves I made was naming my tumor so that I didn't have to use that word anymore. Instead, I chose the name Lazuli, after lapis lazuli, a gemstone native to my ancestral homeland. I didn't yet know about the disability justice movement and how folks had been redefining what it means to have chronic illness in relation to race, class, gender, and sexuality. It felt so good to learn about ableism from the disability justice movement and, coupled with learning about the healing justice movement, it felt easier to advocate for myself against the grain. The university is so incredibly limited and limiting. Historically, women of color were objects of research in higher ed and that's just the thing: the university is an institution that was designed to profit from studying our bodies, whether dead or alive, and with the exception of movement-built niches established from the bottom up like the Department of Ethnic Studies, it continues to function in this way both implicitly and very explicitly.

MF: In what ways did the different name affect your understanding of or emotional response to Lazuli? What feelings or imagined possibilities emerged? Also, what were the disability justice and healing justice movement's specific strategies for redefining and advocating for wellness? In addition to renaming and redefining terminology (perhaps), what strategies did you adopt? Have you, or how have you, continued to reach out to others heavily involved in these movements?

TK: Here is a list of helpful resources compiled by BAVH

Womyn's Circle as Community Building

MF:

What was your criteria when choosing participants for the circle?

TK: The only criteria was that participants identify as womyn. We chose to spell women with a ‘y’ in order to make it clear that for us, cis-women aren't the only womyn.

Otherwise, word of circle spread like wildfire! It started with me and my friends, who were mostly fellow woc* in higher ed, but folks I didn't even know, both on campus and in the community, quickly rolled through by word of mouth. There was a time when we simply couldn't fit anymore folks in my studio apartment! At one point we had a discussion about whether or not to expand circle to accommodate all interested folks but we decided against it. The group's intimacy was one of the main reasons why we felt like we were actually capable of going so much deeper than the surface in a sustainable way.

*[WOC - Women of Color, henceforth WOC]

MF: Would you be able to talk a bit more about the group’s intimacy and how you were able to cultivate it? What were some of the primary ways that the participants connected with one another? What specific themes, under the umbrella of wellness, emerged? In what ways was the sharing process organic and in what ways more structured? Did sharing become collaborative and what insights emerged?

TK: The group's intimacy was a co-created ethic, for lack of a better word. We knew that in order to grow together, we had to be vulnerable, and chose that route individually and collectively.

That meant we had to cultivate a safe space, which I think, is why we always met at my house. Everyone was already familiar with the space and for the most part, with each other, so that definitely set the stage for diving into the deeper stuff. No matter what specific topics emerged, we ALWAYS situated them at the intersection of the personal and the political.

MF: In addition to familiarity with the space itself, how did you cultivate what you determined to be a safe space? Were there "rules" governing the interactions within the space (for example, governing who would speak when and what would be spoken?); if so, what were a few of them? Do you think this safety inadvertently foreclosed certain possibilities, and if so, how did the group reach a consensus over what would and would not happen during circle?

TK: We never formally established community agreements if that's what you mean. In our case, cultivating a safe space didn't foreclose possibilities of healing, which is what we ultimately gathered to do: heal. I've heard academics critique safe spaces, alleging that a safe classroom environment denies controversy and therefore restricts dialogue as well as the potential for students to mature through discomfort. First of all, safe spaces aren't meant to be free of discomfort; they're meant to be free of violence, including discursive violence. It's funny how there's all this brouhaha, from educators no less, about safe spaces in higher ed when the university refuses to repatriate its "collection" of more than 10, 000 human remains stored in the Museum of Anthropology's basement to the Native American communities which the bones, like the very land comprising the Berkeley campus, belong to.

For me, cultivating a safe space is about addressing settler colonialism and committing to decolonization in the service of individual and collective safety as well as liberation. It is a political act that goes far beyond this shallow understanding of safe spaces as a kind of multiculti guidelines for discussion. Safety is in relation to the material impacts of multiple oppressions.

Why can't I ask for a trigger warning when we read Hegel's History of Philosophy in a Critical Theory class? There's so much ignorance within academia about its colonial past, even about its neocolonial present.

MF: What were the participants’ expectations and how did the experience meet, vary from, and/or surpass these expectations?

TK: I honestly can't say what the participants expected...for me, the only expectation was that the space be healing and it was, every single time, far beyond my expectations. We co-created healing practices throughout the process of sharing our experiences, which was in and of itself a form of healing.

I may have put something on the table (like a specific topic), but folks took circle in whatever direction felt right to them. We rotated facilitators who led participants in some sort of activity to start us off. We also always shared snacks as part of our ritual.

MF: Would you be willing to share an example of a healing practice created through this process? That, or an activity facilitated by one of the other circle members that touched you in a profound way? Also, I love that you used the term “ritual” to describe the co-creative process. Did circle draw in part from any specific historical healing traditions and, if so, how did you and others blend these influences in your practices?

TK: Back then, I only had a few books to go off of. Two that I always pulled from for gatherings were Healing With Whole Foods, a book on "traditional Chinese medicine," and Luisah Teish's Jambalaya. Some of the peer led activities included; facilitated free writing, yoga, meditation, dream work, and cooking. I also frequently referenced and used excerpts from This Bridge Called My Back.

MF: What topics were most discussed or most resonated with the participants, and why? Did they correlate with political and cultural events happening at the time? How did the circle's association (if partial or marginal) with the university setting affect the topics explored and what kinds of relations did this association foster?

TK: Circle was non-affiliated throughout its entire existence. The only association it had with the university is that some of us were grad students. This was it's greatest strength, the fact that it was a grassroots project 100% in our control. When I became the WOCI [Women of Color Initiative] Coordinator at the Graduate Assembly, there was thematic overlap with the stuff I organized on campus. That's all though. Of course, since a lot of us were woc in higher ed we did have ongoing and in depth discussion about how academia impacts our wellbeing and how the university is complicit with the medical industrial complex.

Personal, Political, Professional

MF: Did your idea for the circle correlate with your own research interests? How did you (and do you continue to) navigate the experiences and effects of the womyn’s circle in relation to your research and professional life?

TK: Yes! My dissertation research is also about health, about the history of state-sanctioned medical experimentation on woc.

MF: Would you be willing to say a bit more about your work, as well as its questions in relation to those of circle? Did, or how did, circle influence your research and writing processes?

TK: My dissertation research turned out to be historical in large part because of womyn's circle. I started out researching contemporary cases of medical experimentation on woc and quickly realized that I have to situate what's happening now in global histories of settler colonialism and racial slavery so that we can begin to think about say, sterilization abuse in California state prisons as an extension of the past. I wanted to tie this into my research to further debunk the myth that medicine, and science at large, is neutral or somehow outside of history.

MF: Since your dissertation work, have you tied your research and activism to other movements focused on histories and legacies of science-based violence against woc and communities of color in general? I'm thinking about the current struggle over Mauna Kea and other movements focused on relations between communities and land.

TK: Yes :) I'm a sailor working on various projects regarding traditional watercraft within a social justice framework. For me, the ocean contains an archive of the history I conduct research on, as well as a wide range of antidotes to its wounds. My involvement in the contemporary seafaring movement brings it all together in a way that advances social action beyond the state.

Writing to Share and Heal

MF: What kind of subsequent projects have grown from the circle?

TK: One project that grew directly from circle is the Womyn's Circle anthology. It's a finished book that has yet to find a home for publication. We did a lot of free writing together, which inspired me to ask folks for pieces that I might put together in an anthology and that vision panned out with ease. Participants, at this point for a couple of years, were excited to contribute to an archive of our work in the form a book that could support others.

MF: With this exciting book project, what ways do the women address common institutional representations of their health, well being, and sociality in general? What forms did the free writing take--what topics or questions did the group address? Is the book comprised of multimedia? If yes, what forms and in what specific and distinct ways does the multimedia represent and discuss woc wellness and daily life?

TK: It's multimedia! And we're currently looking for a currently registered student to find a small press that will publish it for us! Holler if you know someone! It's a paid gig!

Tala Khanmalek is a Ph.D. candidate in the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley with a Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. As the former Executive Editor of nineteen sixty nine, she published the latest issue on "Healing Justice." Last year she was a Visiting Scholar at UC Santa Cruz's Science and Justice Research Center.